The team behind

the Citroën DS

1925 -1955 Paris

Great cars rarely come from committees, and the Citroën DS is no exception. Although it wore the double chevrons on its boot, the DS was in truth the result of an extraordinary convergence of individuals - engineers, designers, and visionaries - whose combined thinking produced something far greater than any one of them could have achieved alone. At the centre of this constellation were Pierre Boulanger, André Lefebvre, Paul Mages and Flaminio Bertoni.

Pierre Boulanger, Citroën’s managing director from 1937 until his death in 1950, was a quiet strategist. Reserved, ascetic, and fiercely intelligent, Boulanger believed that Citroën should always leap ahead rather than follow. He had already overseen the development of the Traction Avant and the 2CV, both radical in very different ways, and he understood that progress required risk. Boulanger was not an engineer by training, but he had a rare ability: he knew how to recognise genius, protect it, and give it room to work. Crucially, he insisted that any new large Citroën must offer comfort and control on France’s battered post-war roads. From this simple requirement flowed some of the DS’s most extraordinary solutions.

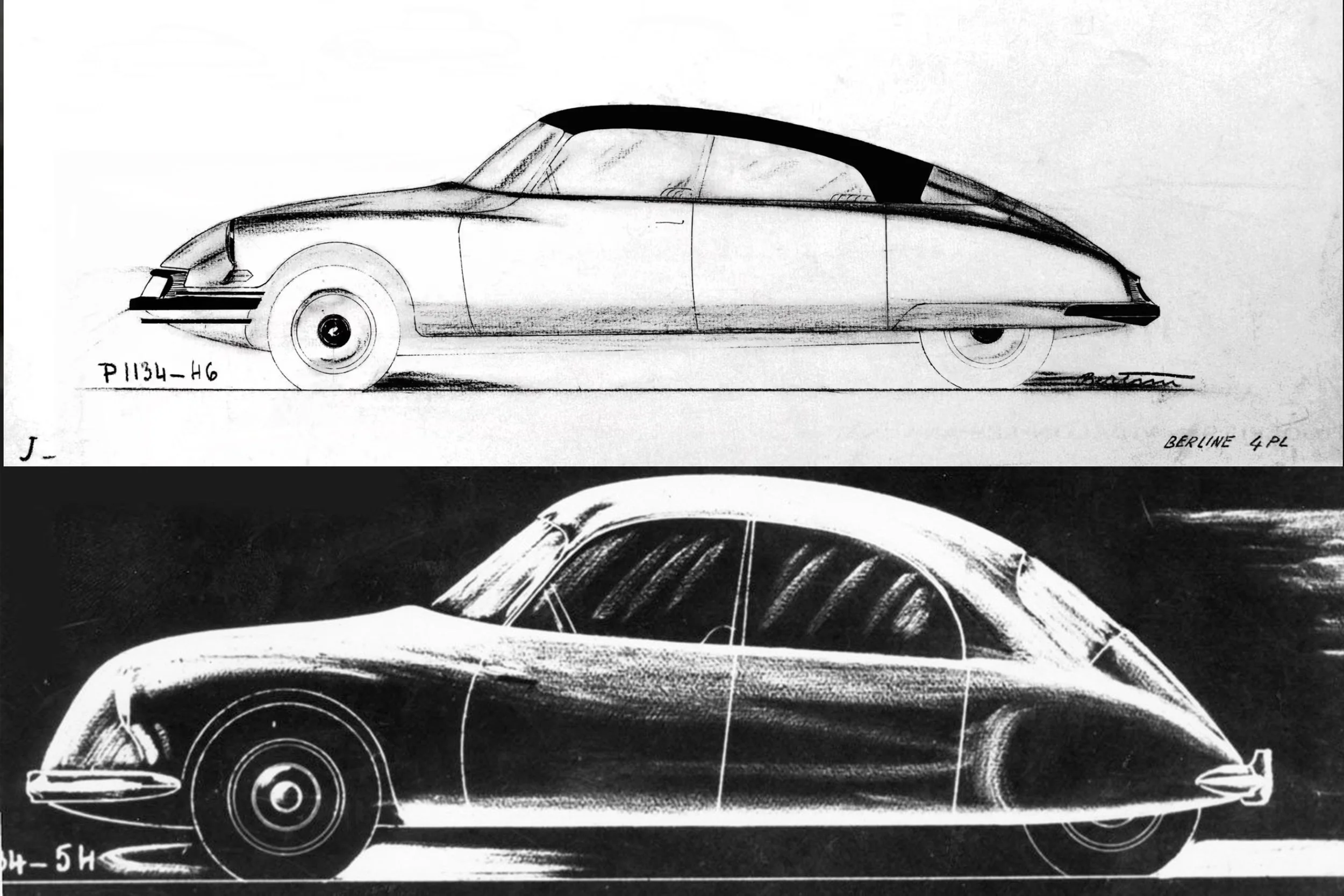

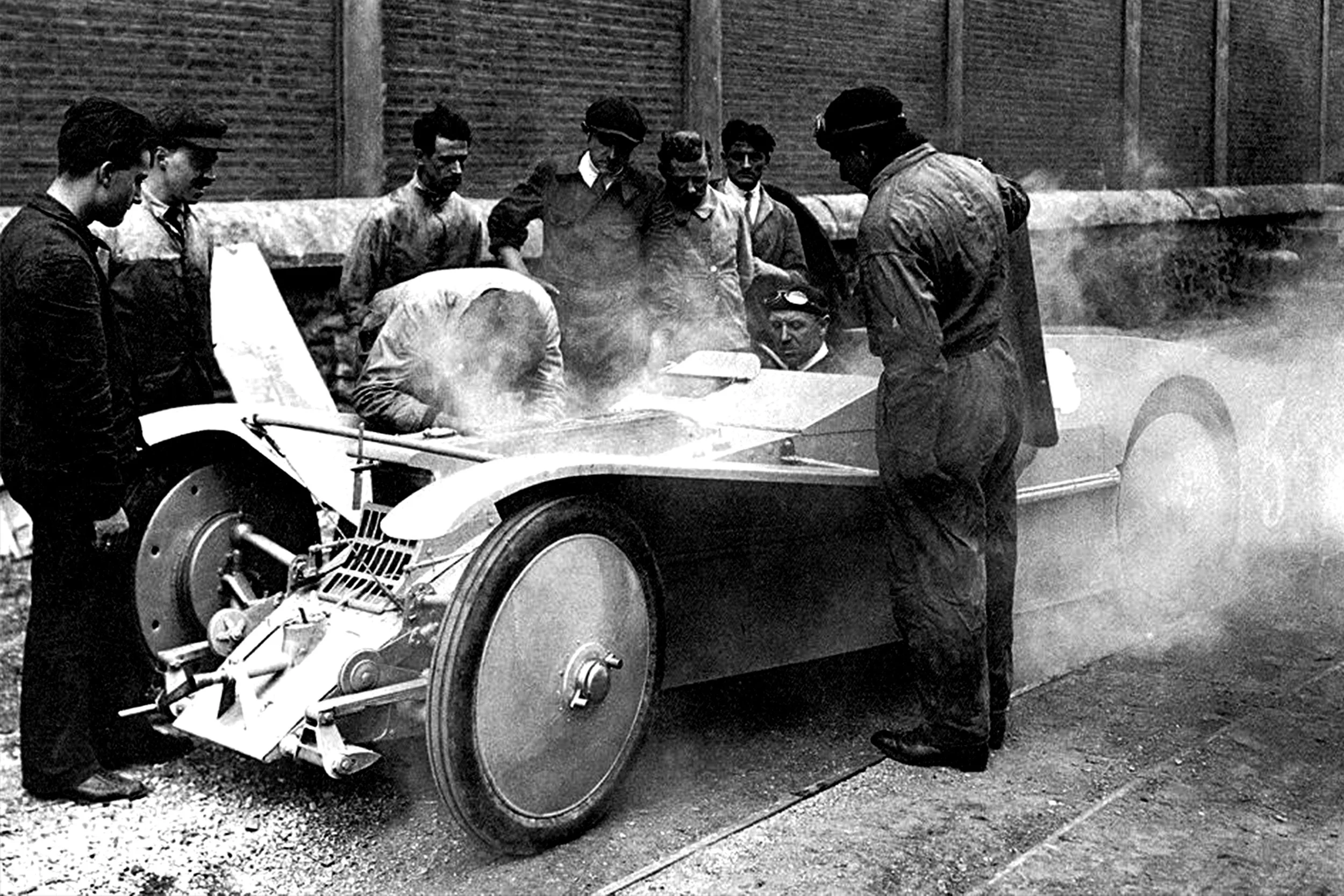

If Boulanger was the conductor, André Lefebvre was the chief theoretician. Trained in aeronautics and formerly associated with Gabriel Voisin, Lefebvre approached cars as flying machines that happened to touch the ground. Weight, balance, airflow and efficiency mattered more to him than convention or appearance. He had already brought front-wheel drive and monocoque construction to mass production with the Traction Avant, and his thinking for the DS went further still. Lefebvre imagined a long, low, aerodynamically clean car with minimal mass, exceptional stability and a suspension system that could isolate the body from the road altogether. Many of his ideas seemed implausible, even reckless, but history would prove him right.

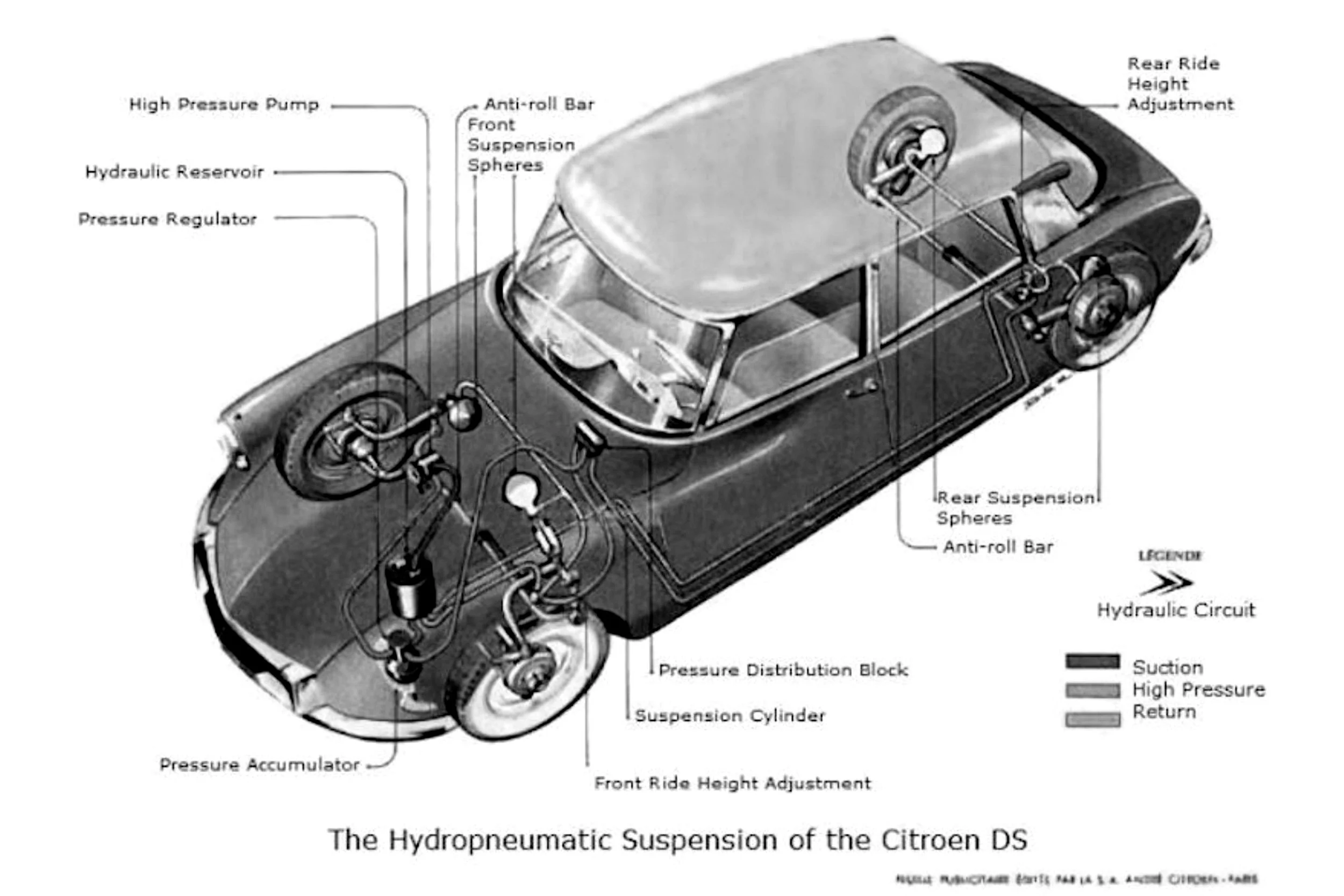

That suspension – the feature most closely associated with the DS – was the work of Paul Mages, one of the great unsung engineers of the 20th century. Although Mages was not formally trained as an engineer, he possessed an intuitive grasp of hydraulics that bordered on the instinctive. Beginning in the 1930s, he developed the idea of using pressurised fluid and gas not just for braking or load control, but as a complete replacement for conventional springs. The result was the hydro-pneumatic (more accurately oleo - pneumatic) system: self-levelling, load-independent, and capable of delivering a ride quality unlike anything the world had seen. For Mages, hydraulics were a unifying principle – a single pressurised system could power suspension, steering, braking and even gear selection. It was elegant, logical, and terrifyingly ambitious. Marcel Pagnol, the French playwright, famously said "Everyone thought it was impossible, except an idiot who did not know and who created it." Magès kept a copy of this statement on his desk.

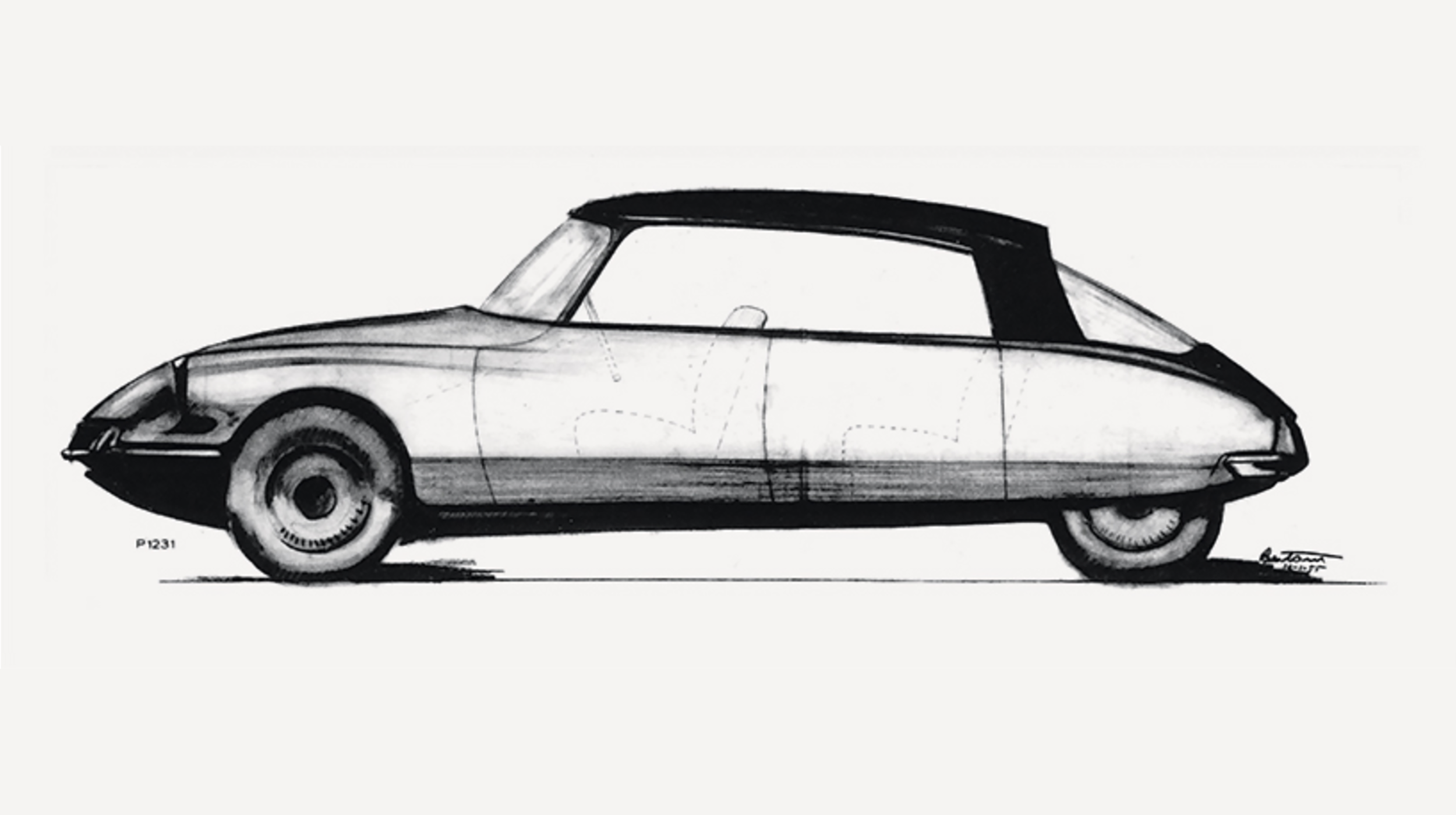

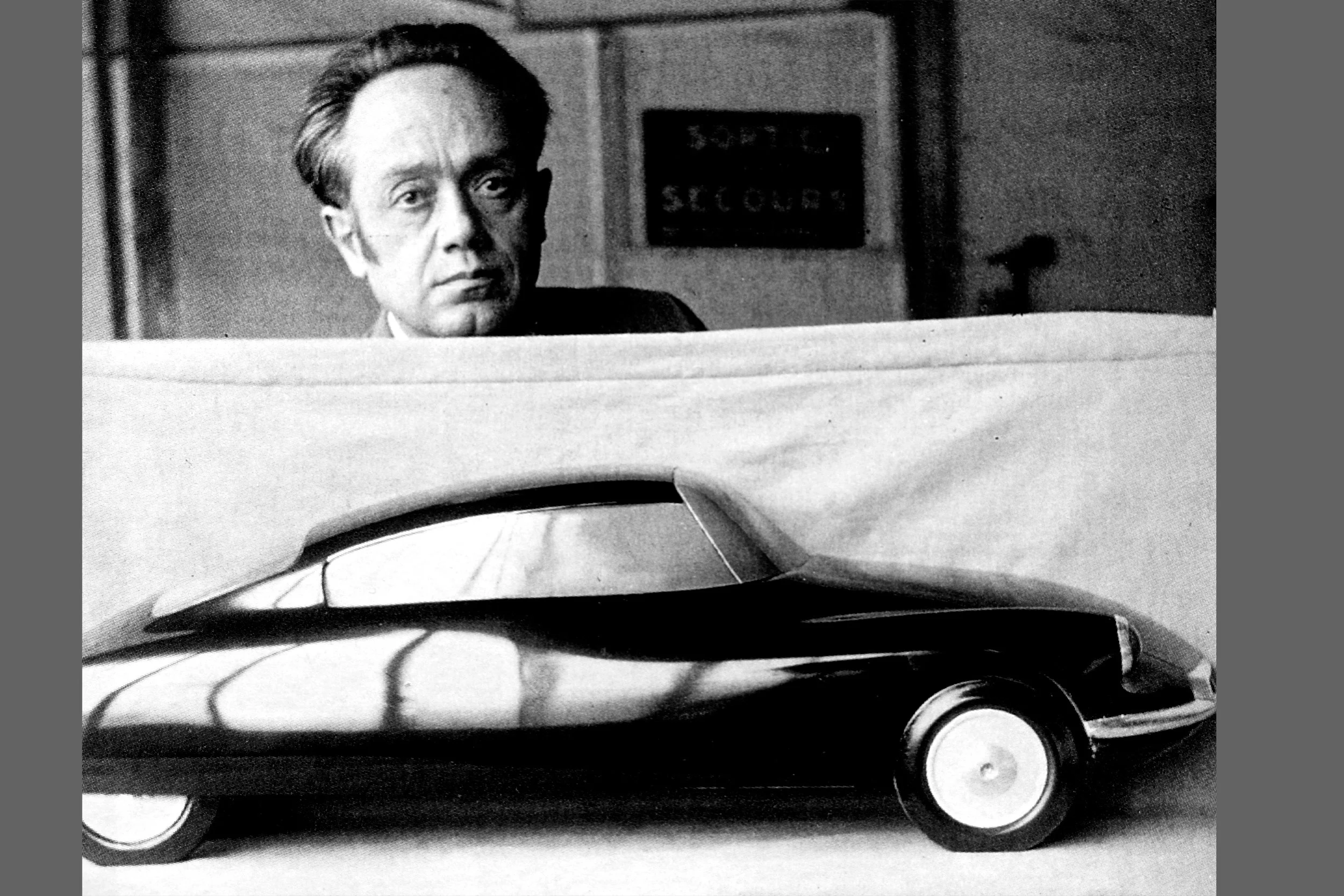

If Lefebvre and Mages defined how the DS worked, Flaminio Bertoni defined how it looked – and, in doing so, how it felt. Bertoni was a sculptor first and a car designer second. Working largely by eye and hand rather than formula, he shaped the DS as if it were a living thing, drawing inspiration from aerodynamics, hydrodynamics and nature itself. The result was neither decorative nor fashionable, but deeply coherent. The DS did not look fast or luxurious in the conventional sense; it looked inevitable. Bertoni’s genius lay in translating Lefebvre’s technical demands into a form that was both radical and beautiful, without ever appearing forced.

Around these four central figures was a wider team whose contributions were just as vital: body engineers such as Pierre Franchiset and André Estaque, who turned daring concepts into manufacturable reality; sculptors and model-makers like Henri Dargent and Raoul Henriques Raba, who refined the DS’s form in plaster and clay; and later designers such as Robert Opron, who would sensitively evolve the car without betraying its original intent.

What united all of them was a shared belief that the motor car could be something better than it was. Not louder, not flashier, not more powerful for its own sake – but more intelligent, more humane, and more forward-looking. The DS was not designed to impress in a showroom alone; it was designed to change expectations.

That is why the DS still feels alive today. It is not merely an object from the past, but a record of a moment when imagination, courage and technical brilliance aligned. In the DS, Boulanger’s strategic vision, Lefebvre’s aeronautical logic, Mages’s hydraulic genius and Bertoni’s sculptural eye came together in perfect, improbable balance. Cars like this do not happen often – and when they do, they leave a long shadow.